The holy trinity of the author, the audience, and the main message presides over every passage ever written. However, in his essay “The Death of the Author”, Roland Barthes argues otherwise: the author’s intentions and personal life, he claims, should not be considered when interpreting a work. According to Barthes, the author doesn’t exist before their text like a godly father; rather, they are only created when a reader consumes their text.

This isn’t to say that every time you read Fahrenheit 451, a baby Ray Bradbury plops into this world. Instead, with the concept of the Death of the Author, we acknowledge a distinction between Bradbury as the author of Fahrenheit 451 and Bradbury as a regular man. The voice of the novel that we “hear” in Fahrenheit 451 is not Bradbury’s; it is Bradbury’s language that tells us the story of Guy Montag, not Bradbury himself.

a.k.a. what is the concept of death of the author?

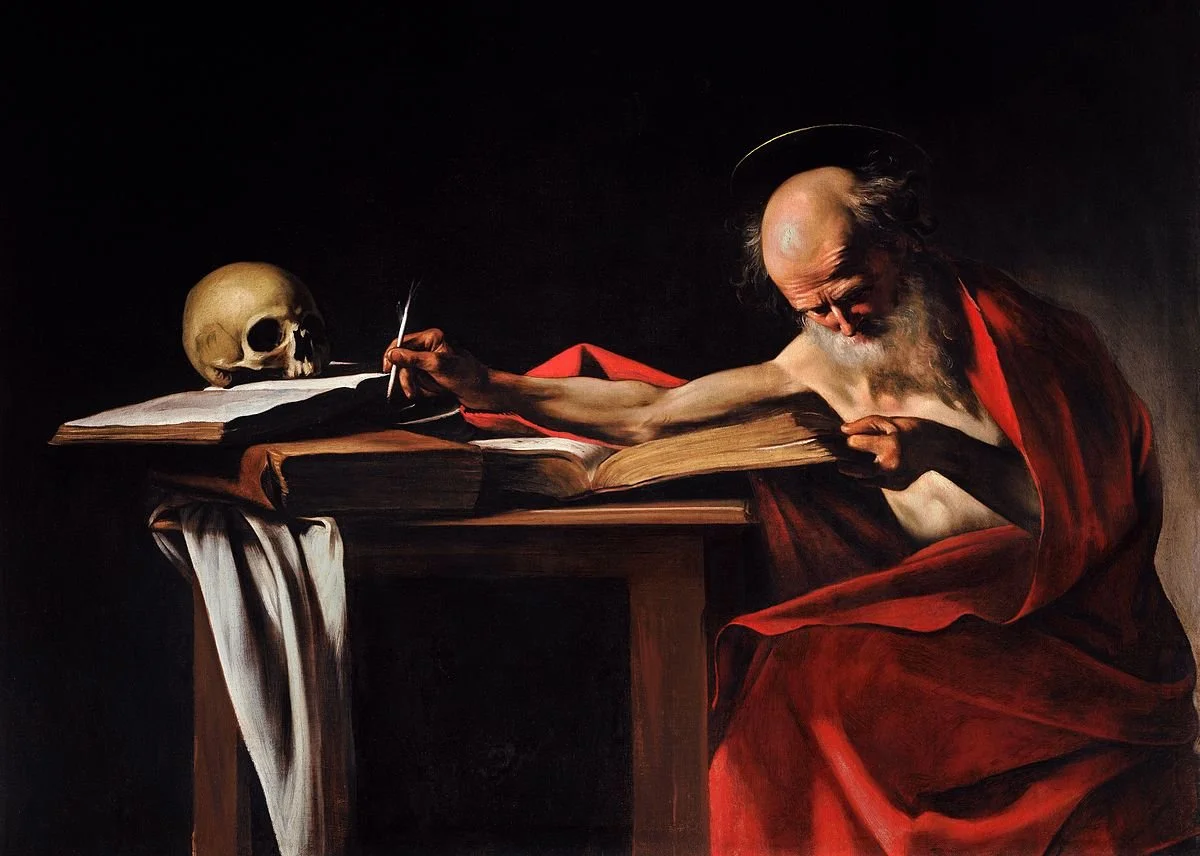

St. Jerome Writing by Caravaggio (with some rather convenient symbolism)

To parallel the example Barthes uses in his essay, when we read The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the women in the story (Daisy, Jordan, and Myrtle) are depicted as materialistic, dishonest, and shallow. Is this an indication of Fitzgerald’s misogyny? Is this unflattering depiction indicative of the societal views of the 1920s? Is it part of Fitzgerald’s characterization, in which case it’s Nick Carraway who’s misogynistic? The point is, we don’t—and can’t—know. To try to factor in the author’s original intention is both impossible and limits the reader’s interpretation, and it is the reader who gives the work its meaning.

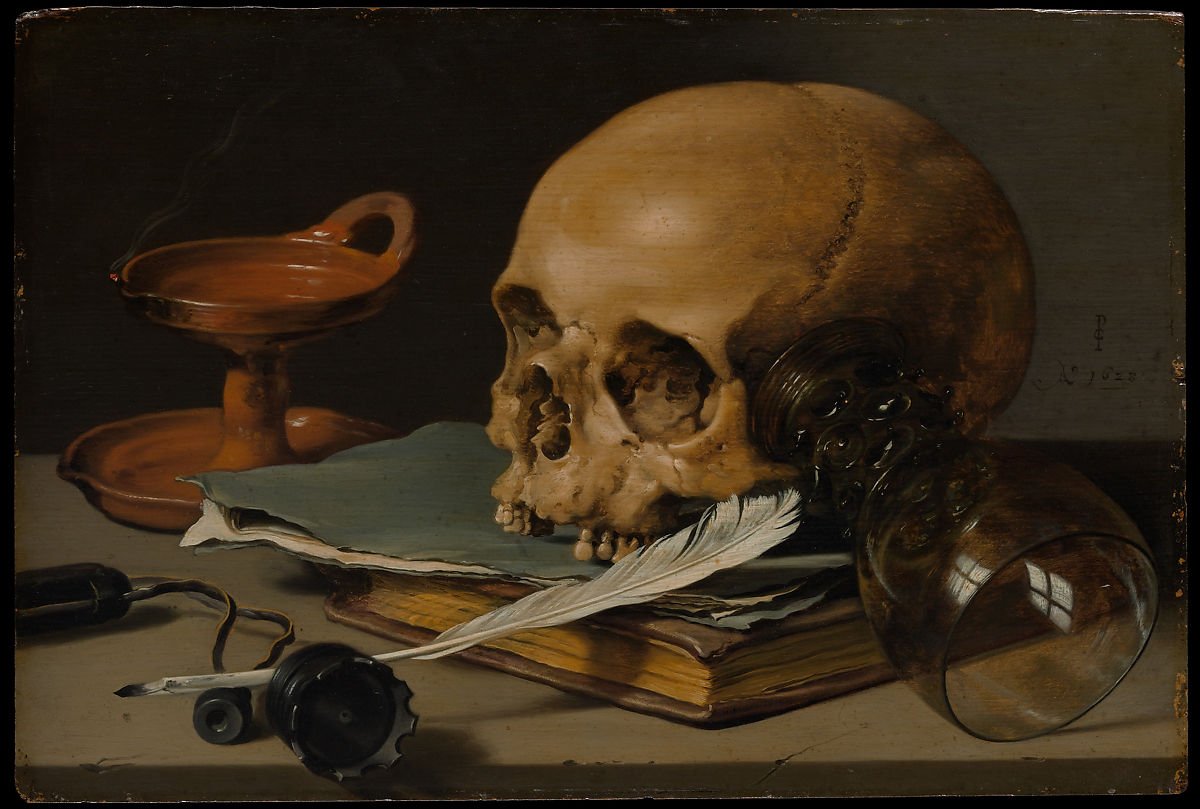

Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill by Pieter Claesz

Okay, this guy says the author’s intent doesn’t really matter.

…so what?

To be honest, if you couldn't care less about literature, you could never think about Roland Barthes or the Death of the Author ever again and live a perfectly good and very fine life. It may seem like a somewhat stupid concept—wouldn’t the author know what’s going on in something that they wrote?— and obviously, there are a number of counterarguments and rebuttals and qualifications, but it's an interesting position to consider on an issue that seems to have a bygone conclusion.

Ex: When Ray Bradbury insists that Fahrenheit 451 isn’t actually about censorship and is instead about the threat of mass media, should that influence our understanding of the book? Clearly, he has some modicum of knowledge about a novel that he wrote, but once the book is published and read, it’s arguable that it’s not really under his jurisdiction anymore. At a certain point, the novel has to stand for itself; it’s the novel that we analyze, not Bradbury’s inspiration and intent.

Webpage design by JOYCE MA